Fifty-six years ago, on a cold and windy day in Washington, eighty-six-year-old Robert Frost stood to read “Dedication,” a poem he had written for the inauguration of John F. Kennedy. Squinting into the bright sun, he found himself unable to read the faint type in front of him, and so instead he recited an earlier poem from memory. “The Gift Outright” is a far better poem, more succinct and more complex in its depiction of America.

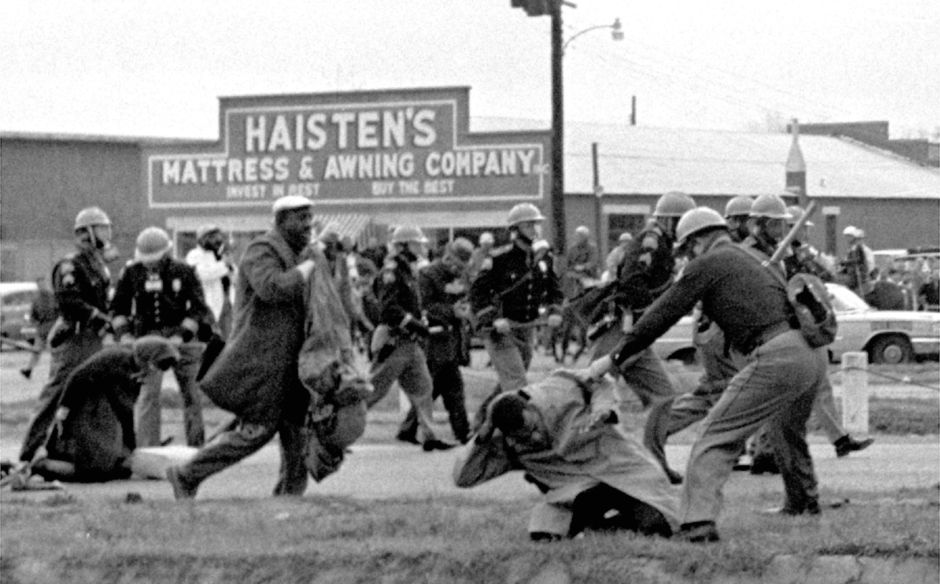

It’s a poem worth pondering, especially today, about the connection between Americans and their land – not just about the repository of vast resources to be exploited for great wealth, but about the still-unfolding story of ourselves as a people. What’s missing, as in so many of our stories, is the remembrance that the land the Europeans found was not empty, was not “unstoried, artless, unenhanced,” but filled with people we displaced and often worked by people we enslaved.

Maybe that’s because we possessed the land before we gave ourselves to it, because we mistook a gift to be shared for a possession to be hoarded, even defining an entire people as private property.

It is said these days that people only want to read the news they agree with. We have always approached our history the same way, leaving out the things we don’t want to remember. But we will only, I believe, appreciate the gift that is America when we embrace all of its messy, deplorable, inspiring story. Then perhaps we will find “salvation in surrender.”

The Gift Outright

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,

Possessed by what we now no more possessed.

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living,

And forthwith found salvation in surrender.

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.