Animal Kingdom Farm Plantation

“In wildness is the preservation of the world,” Henry David Thoreau

Read More“In wildness is the preservation of the world,” Henry David Thoreau

Read MoreNinety-two years ago yesterday, Edwin Hubble announced the discovery of V1, the first star anyone had ever seen in a galaxy beyond the Milky Way. Called “the most important star in the history of cosmology,” it turned our world upside down. Piers Sellers died on Dec. 23rd at the age of 61. Vera Rubin died two days later. She was 88. Both were scientists who spent a lot of time out among the stars, an experience that made them feel humble about humankind’s place in the vast cosmos, stunned by the beauty of the earth and, and yet ever hopeful.

Sellers, a naturalized American citizen who made three trips to the Atlantis space shuttle, died less than a year after being diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer. He spent much of that year trying to awaken people to the reality of global warming.

Still, he said of his short life and looming death, “I’ve no complaints. As an astronaut I spacewalked 220 miles above the Earth. . . .I watched hurricanes cartwheel across oceans, the Amazon snake its way to the sea through a brilliant green carpet of forest, and gigantic nighttime thunderstorms flash and flare for hundreds of miles along the Equator. From this God’s-eye-view, I saw how fragile and infinitely precious the Earth is. I’m hopeful for its future.”

Rubin was an astronomer who looked out from the earth as far into space as she could see. She saw so far she reached the limit of her sight; and that was when she realized that most of what was out there – literally millions of other galaxies – was invisible to her. “I’m sorry I know so little,” she once said. “I’m sorry we all know so little. But that’s kind of the fun, isn’t it?”

Far from being the center of the universe, we are infinitesimal, fleeting blips on a vast cosmic screen. And yet, for Rubin and Sellers, that fact is not a reason for despair, but for hope, even fun. In these times of strutting egomania, perhaps realizing how small we really are is the first step toward wisdom.

“Each one of you can change the world,” Rubin told the 1996 graduating class at Berkeley, “for you are made of star stuff, and you are connected to the universe.”

Happy New Year.

Ah, another beautiful sunny fall day.

Read MoreTwo reasons I believe the market system can play a vital role in building a better economy are: (1) it spawns entrepreneurs – the loner in a garage, the small group in a laboratory, the back-to-the-land organic farmer – in a way no other economic system ever has; and (2) incentives, economic and otherwise, work for most people, and I believe they can work for the common good.

Read MoreYesterday I ended my post with the following sentence: “We don’t treat air as a commodity to be owned, bought and sold by powerful people, so why water, which is equally essential to all living things?” Then my old friend, Jock, sent me this: “Canadian start-up sells bottled air to China, says sales booming.”

Read MoreThose of you who drink Fiji water, drink P♥M juice or eat nuts may want to skip this post about water and the Wonderful Company, the California-based agribusiness empire of Lynda and Stewart Resnick.

Read MoreIn Acadia National Park, which is about to turn 100, the streams are abnormally dry, the waterfalls unseasonably quiet.

Read MoreWith climate change reduced to a derisive footnote by Republican candidates and Congressional majorities, you may have missed recent reports of 2015 being the warmest year ever recorded (overtaking, um, 2014); missed the study on the worldwide demise of coral reefs; and missed new research updating the alarming state of the Antarctic ice sheet.

Read More

Flint’s water is back in the news, now politically as well as physically toxic. “The Birthplace of General Motors” is perhaps the most beleaguered city in America: 40% of its people in poverty; crime and unemployment almost triple the national rates; a city unrecovered from the 2008 housing catastrophe. It’s a place you leave if you can (its population is half what it was in 1970) – but that’s not easy for homeowners facing plummeting housing values.

Two years ago, the state-appointed emergency manager switched Flint’s freshwater source from Lake Huron to the Flint River for one reason: to save money. Dirty water should be cheaper than clean water, right?

Not in Flint, which has the most expensive water in the country. As in much of America, both urban and rural, poverty and environmental vulnerability go hand in hand.

Clearly, Flint requires a lot of economic investment, much of it to rebuild its decayed infrastructure, but don't hold your breath in these anti-government times. But we should think beyond vast engineering projects. Particularly when it comes to water, using nature’s infrastructure is a far better way to go – for if we take care of our upstream watersheds, their streams and rivers can actually process pollutants and clean their own water.

Almost 20 years ago, New York City also faced a water and financial crisis. Instead of building a multi-billion-dollar filtration plant for its 9 million users, it invested a fraction of that amount to protect its water sources up to 100 miles away. The result is cleaner and cheaper water.

In the long run, Flint’s water doesn’t need more chemicals; it needs cleaner sources.

Some things are worth waiting for. My son Jake sent me an announcement of the successful efforts of 26 indigenous tribes, five timber companies and four environmental groups to protect the magnificent 12,000-square-mile Great Bear Rainforest on British Columbia’s Pacific coast. The negotiations were arduous, and they took 10 years.

Read MoreWhen I last visited Flint, Michigan, in 2012, I wrote in American Apartheid: “Flint belies our image of urban decay. With no high-rise projects, it is a city of tree-lined neighborhoods of single-family houses where 200,000 people once lived, and half that number remains. But on those streets are hundreds of abandoned and burned-out houses, which remind you that Flint is the most violent city in America.” Flint is back in the news, this time because, in April 2014, its state-appointed emergency manager switched the source of the city’s water to the Flint River to save money. The water was cheap because it was filthy, and the complaints began immediately. Soon the city was telling its residents to boil their water before drinking it, and General Motors stopped using it altogether because it corroded engine parts. But the state government ignored the growing health crisis until it became a full-blown political disaster.

Flint is where environmental degradation meets social neglect. For over five decades the city, the birthplace of General Motors, has suffered the all-too-familiar urban pattern of disinvestment, depopulation and decay, unemployment, poverty and crime.

For a long time in this country, the environmental and social justice movements ran on separate tracks, focusing on different wildernesses. But it’s increasingly clear – from climate change to Flint’s water supply – that the first victims are the same: the poorest and most vulnerable, those who can neither move nor get out of the way. When governments deliberately abandon those people, it seems a betrayal of democracy.

We raised our kids in southeastern Pennsylvania, which was still largely rural, although the influence of the DuPont Company radiated powerfully from its Wilmington base 18 miles away. Many family members and company executives lived in Chester County, whose jewel is Longwood Gardens, once the country estate of Pierre du Pont and now one of the world’s botanical wonders. DuPont was considered a good corporate neighbor. Family members and employees served on many community boards, and earlier generations had created foundations that were particularly active in land conservation and environmental protection. The company itself had the reputation of being a leader in industrial sustainability and corporate best practices.

That reputation fell apart this month with Nathanial Rich’s revelation of DuPont’s decades-long efforts to conceal the environmental and human costs of its chemical pollution. “They knew this stuff was harmful,” said attorney Rob Bilott, “and they put it in the water anyway.”

You’d think we’d be inured to these stories by now. From the cigarette companies to Dan Fagin’s Tom’s River, 60 years of a single, numbing plot line: cover-ups, bullying and lying through their teeth. “I always thought [DuPont] was among the ‘least-worst’ of the polluters,” the former editor of the local newspaper wrote me. “Turns out they were horrendous” – not in their own backyard, of course, but in West Virginia where they thought nobody would notice.

I don’t think DuPont set out to be a bad neighbor, but before succumbing to the siren song of deregulation, it’s worth pondering how it became one.

Yet, what I will remember most about Doug is his passion – a passion that fueled his drive for perfection in everything he did. That didn’t make him easy to work for. He was as cantankerous a person as I have ever met, and he rubbed many people the wrong way. But in the end he was driven by love – love for the land he fought to protect, love for the people who fought with him, love for Kris, his partner in everything.

Read MoreDrought is not the only – and perhaps not even the primary – cause of Syria’s violence, but water is as important a part of the equation in the Middle East as oil.

Read More“The health of our water is the principal measure of how we live on the land.” Luna Leopold While Texans brace for Emperor Obama’s military invasion, Californians continue to pray for rain. With 93.4% of the state in its fourth year of “severe drought," a beautiful sunny day is an oxymoron and the clouds have no rain.

Carly Fiorina knows why. The latest contestant in the Republican presidential sweepstakes, Fiorina’s main claim is that she ran Hewlett-Packard into the ground, the difficulty of which should not be underestimated. Her analysis of the drought is equally unsettling. “Droughts are nothing new,” she wrote recently. The problem this time is not nature. It’s people, specifically “overzealous liberal environmentalists” whose policies “allow much of California’s rainfall to wash out to sea” instead of being diverted to Central Valley cantaloupe farmers. “It comes down to this: Which do we think is more important, families or fish?”

This is nonsense. Anyone who thinks that a drop of water making it to the ocean is wasted should visit the once-mighty Colorado, which has been so thoroughly dammed and diverted (4.4-million acre feet a year to California alone) that it hasn’t flowed regularly to the sea since 1960. Its estuary has become a poisoned trickle. We’re the problem all right: we’re killing the river.

A river is not a pipe. It’s an ecosystem that, if we care for it, will return huge benefits – including fish. Our health depends on its health. The answer, Ms. Fiorina, is “families and fish.”

No issue better reflects the growing chasm between America’s two political parties than that of the environment, which was born in the Republican Party and was once a broadly bipartisan issue. The 1972 Clean Water Act, for example, passed the Senate, 86-0, and the House, 366-11 – and then easily overrode Richard Nixon’s veto, 57-12 and 247-23. But the League of Conservation Voters’ latest National Environmental Scorecard tells a completely different story, particularly in the House of Representatives, where most Democrats score above 90%, most Republicans below 10%. Among the leadership the difference is even starker – with Democrats at 92% and Republicans at 2%. And there’s a nice consistency among the declared presidential candidates: Cruz 0%; Paul 0%; Rubio 0%. The partisan differences are escalating for two reasons: (1) most Republicans’ current scores are significantly lower than their lifetime averages (Oregon’s Greg Walden has dropped from 11% to 3%, for example, and Virginia’s Frank Wolf from 26% to 6%); and (2) the tea party wing is pushing the GOP deeper into anti-environmental territory. Many House votes now attempt to roll back existing protections – keeping pesticides out of our waterways, for example, and carbon pollutants out of the air. Others seek to prevent the Defense Department from replacing fossil fuels with biofuels and the EPA from using peer-reviewed scientific studies with confidential health information.

This creates a dilemma for the League, as it tries to maintain a semblance of non-partisanship, something it has traditionally done by supporting Republicans with mediocre records – like Maine’s Susan Collins (55%) – over pro-environment Democrats. Such Republicans are ever harder to find.

In Ireland they don’t call it the famine – those years in the mid-19th century when English landlords exported huge quantities of grain and beef while a million Irish people were dying of starvation and a million more were leaving their homeland. They call it “the great hunger” because the blackened blight of the potato, the lone food on which peasant lives depended, caused massive suffering in the midst of agricultural plenty. It wasn’t a famine. It was a policy. So we read now of California, whose farmers produce most of America's fresh food, consume four-fifths of the state’s vanishing water, and are exempt from Gov. Jerry Brown’s mandatory water restrictions. California, where almonds, the most lucrative export, use 1.1 trillion gallons a year, where it takes 872 gallons of water to make a gallon of wine, 1,847 gallons for a pound of beef, and 4.9 gallons for a single walnut.

The drought is real in California, its end is nowhere in sight. And while farmers didn’t stop the rain, longstanding agricultural policies and practices exacerbated the long-predicted crisis.

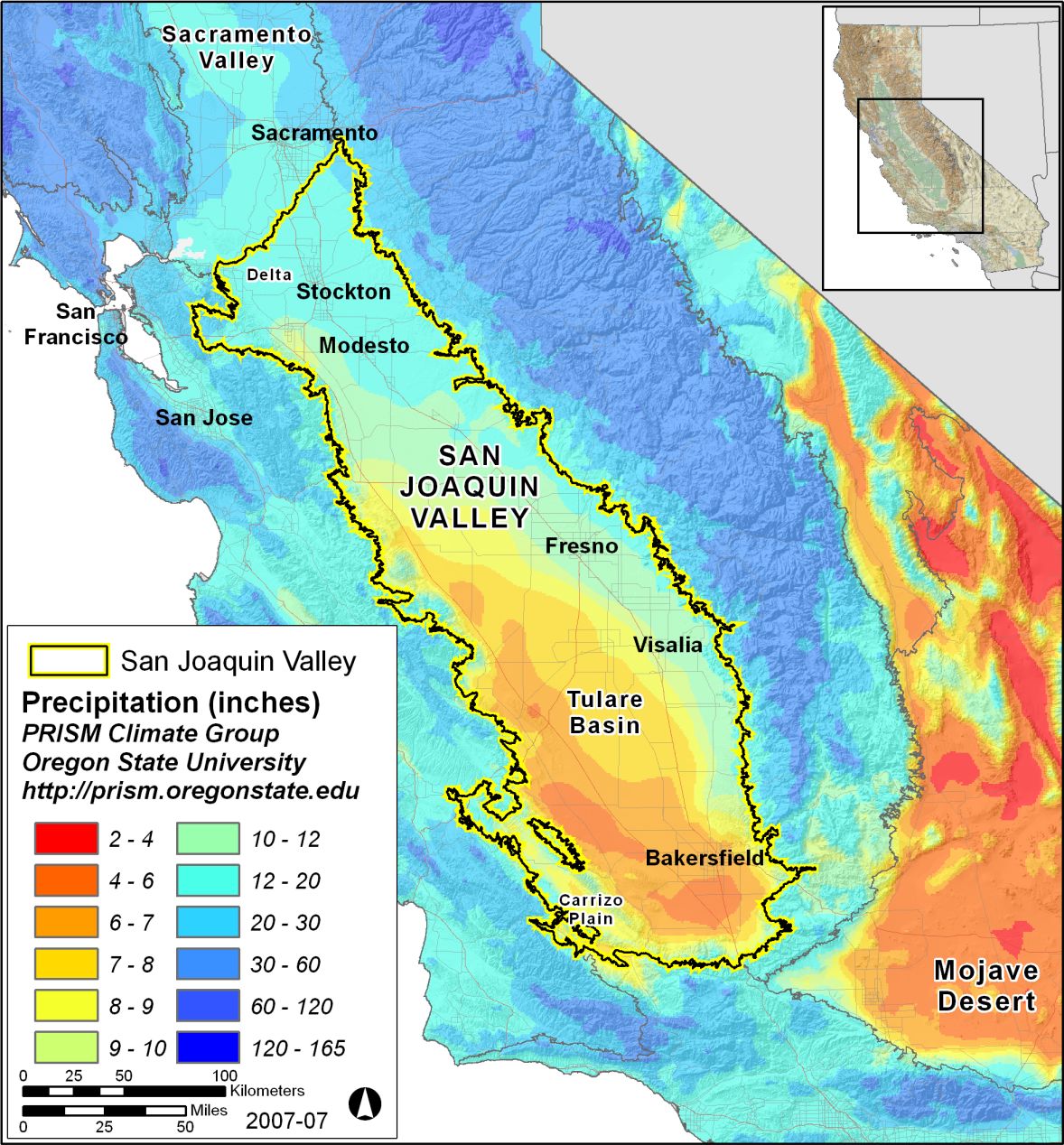

The San Joaquin Valley didn’t become “the nation’s salad bowl” on its 15 inches of annual rain. It took massive irrigation projects and the diverted waters of the Colorado River to make the southwestern desert bloom. And it is one more testament to what Marc Reisner, in Cadillac Desert, deemed “the West’s cardinal law: that water flows toward power and money.”

Sometimes I wonder whether Mitch McConnell used to ask Santa to put a lump of coal in his stocking. He certainly does love the stuff and those who sell it. (They don’t “produce” it; the earth does that.) And while the rest of the world is trying to reduce its dependence on coal, the Majority Leader is on a single-minded crusade to ensure we keep burning as much as we can. It's good for us. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, an average-sized coal plant annually discharges: 3.7 million tons of carbon dioxide (the equivalent of chopping down 161 million trees); 10,000 tons of sulfur dioxide; 10,200 tons of nitrogen oxides (equal to 500,000 new cars); hundreds of pounds of mercury, arsenic, lead; and on and on.

Last week McConnell wrote all 50 governors, urging them to simply ignore the administration’s regulations aimed at a 30% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030, adding that “the real danger [is] allowing the EPA to wrest control of a state’s energy policy.” This is part of a political and legal counterattack on President Obama’s “war on coal,” and it's not to be taken lightly. Laurence Tribe, Obama’s Harvard Law School mentor, testified that the EPA’s “energy” plan amounted to “burning the Constitution,” an issue likely to appeal to five Supreme Court justices I could name.

But EPA stands for Environmental Protection, not Energy Production, and as the Nixon administration learned 45 years ago, it requires a national effort to safeguard our air and water. We need one now.

The plunging price of oil has already had a number of consequences, including:

Perhaps above all, $45-a-barrel oil threatens to aggravate the historic liberal divide between those focused on social justice and those dedicated to environmental protection. At least as far back as John Muir’s battle to stop the Hetch Hetchy dam, economic and environmental progressives have had a wary, often antagonistic, relationship. The latter’s emphasis on wilderness and endangered species protection has often seemed in conflict with the social and economic needs of the poor and unemployed. The environmental justice movement arose to bridge that divide, arguing that the poor suffer disproportionately from environmental degradation and insisting that the fate of the earth and the welfare of its people is not about choosing one or the other.

But cheap gas has a way of making people ignore the real costs of energy consumption; and so today we do have a choice: we can burn these momentarily cheap fossil fuels like there’s no tomorrow or we can use this fortunate interlude to build a better one.

We could start with a gas tax.