A River and Its Water: Reclaiming the Commons - Part 25

25th of a series

“If you are against a dam, you are for a river. . . . Let the mountains talk, let the rivers run. Once more, and forever.”

- David Brower

“In the view of conservationists,” writes John McPhee in Encounters with the Archdruid, his wonderful three-part profile of David Brower, the first executive director of the Sierra Club and later founder of Friends of the Earth, “there is something special about dams, something . . . disproportionately and metaphysically sinister.

“The conservation movement is a mystical and religious force,” he continues, “and rivers are the ultimate metaphor of existence, and dams destroy rivers, humiliating nature.”

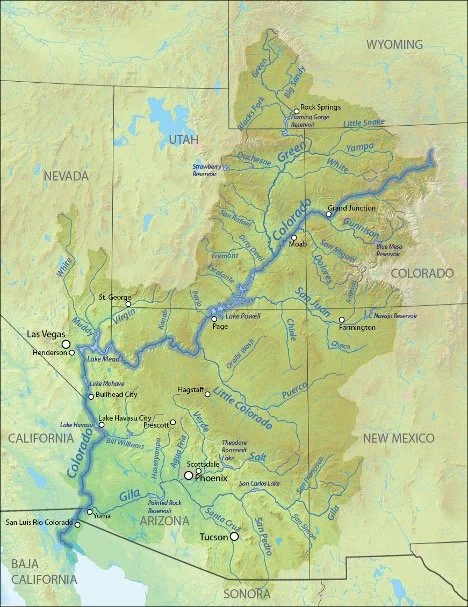

In “Part 3:The River,” McPhee joins Brower and Floyd Dominy, the equally-larger-than-life director of the Bureau of Reclamation, on a raft trip down the Colorado River. In a nation of huge dams, Dominy is their primary builder and most powerful cheerleader. Brower hates them.

“The Bureau of Reclamation engineers are like beavers,” he says. “They can’t stand the sight of running water.”

“Reclamation is the father of putting water to work for man,” Dominy counters, chewing on a gigantic cigar. “Irrigation, hydropower, flood control, recreation. Let’s use our environment. Nature changes the environment every day of our lives – why shouldn’t we change it. We’re part of nature.”

Their conversation, by turns combative and respectful – and always lively – epitomizes the two sides of a critical social and environmental dispute: the relative merits of a natural vs. an engineering approach to providing water to humans while also protecting its sources. The river itself frames the conversation: as their raft makes its way downstream, they pass through the Grand Canyon, one of the seven natural wonders of the world, and then on toward the Hoover Dam, completed in 1936, and still one of the seven engineering wonders of the world.*

New York City’s water system represents an effort to combine the two approaches: an enormous infrastructure of reservoirs, pipes, dams, and aqueducts in a landscape kept undeveloped to protect the sources of the water. But it’s a stretch to think of the system as natural when you consider how much earth moving and heavy equipment it took to create it – until you compare it to other enormous engineering solutions, from dams to desalinations, whose primary aim is to overwhelm natural “obstacles.”

Dams are an interesting case. They have provided many benefits to humans, including hydropower, irrigation, flood control, and water storage. But a half century after their heyday, when Dominy was heralding them as the pathway to the future, we have learned much about the harm they cause, from sediment build-up to fish extinction to greenhouse gas emissions. “The environmental consequences of large dams are numerous and varied,” reports International Rivers “and include direct impacts to the biological, chemical and physical properties of rivers and riparian environments.” Here we are, back at Robin Vannote’s River Continuum Concept, which proposed that all riverine life is connected. “Fundamentally,” reported the state of Vermont, “the dam is a barrier that interrupts the natural river dynamics.”

In McPhee’s telling, Floyd Dominy is the P.T. Barnum of progress, David Brower the Cassandra of doom. Looking back over the years, as scientists have discovered more and more about the dynamics of streams and rivers, Brower, the curmudgeon trying to hold back the future, seems less and less a troglodyte and more and more prophetic.

*Seven natural wonders of the world: Aurora Borealis; Harbor of Rio de Janeiro; Grand Canyon; Great Barrier Reef; Mount Everest; Victoria Falls; Parícutin, Mexico.

Seven engineering wonders of the world: International Space Station; Golden Gate Bridge; Channel Tunnel; Burj Khalifa, Dubai; Great Wall of China; Hoover Dam; Millau Viaduct, France.